It is a beautiful spring day. Tulips have emerged from their winter dens and I finally feel warmth in the sun’s rays. To do some chores I jump in the car and I drive south on Lincoln Avenue. As I pass the local Dominick’s I glimpse a woman in the attire of the Middle East. A hijab covers her head, but I see her face in the shadows. The first thing I think of as I look into her eyes, the only thing I think of, is suffering.

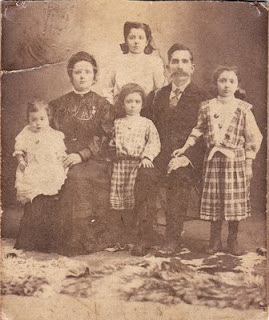

In an instant I am reminded of my Italian heritage. My grandparents immigrated in the Italian Diaspora that saw millions pass through Ellis Island. We have all seen the eloquent black and white photographs of huddled women and their children waiting to be allowed onto the mainland of America. These were my relatives.

Almost all of my grandparent’s children were born in Italy with my parents being the exceptions. My grandpa Pasquale was from Collodi, a small hill town in Tuscany where the author of Pinocchio was born, and my grandma Viginia came from yet another small hill town, Aragona, located in southwest Sicily.

A striking remembrance of my youth is that none of my relatives, at least the ones who were born and raised in Italy, ever talked about the old country. Nor were they interested in going back for a visit. Despite their joy in sharing food and wine together they had a desperate air about them that I never could quantify.

Although none of them confided in me, I think their countenance was mainly due to suffering. America is populated by a multitude of ethnic groups. Many of which have one thing in common: suffering at the hands of despots, poverty, war, religious persecution, torture, slavery, and in the Japanese community, internment.

What are we to make of a country full of such desperate people. Desperate to find stability, desperate to ensure that their children will not suffer their same fate, desperate to find a country with a legal system not predicated on the whims of a ruling elite, and paradoxically, while searching for the freedom to live their lives the way they want to, they are also desperate for their children not to lose their traditions.

And herein lies the contradiction. Right-wing commentators speak hysterically about the loss of values due to immigration, but after a couple of generations most offspring are indistinguishable from the rest of us. Just as I have lost much of my “Italianism”, so have the students I teach lost their Indian, Chinese, Pakistani, Vietnamese and European traits. I believe that deep inside their ethnic identities still exist, but on the surface they are as good a consumer as the rest of us.

Our parent’s culture becomes important at the milestones of life: weddings, funerals, confirmations and births. It is then that cultural differences in mixed relationships begin to surface. It is then that now grown children become horrified with realization that they are acting like their parents. Suddenly the values they share with their ancestors become important and they search for a way to pass their culture on to their children.

In many situations this compunction skips a generation. The first generation in America strives to fit in, earn a living and educate their children. The second and third generations try to reinvent their parent’s culture. They are the ones who research the genealogy of the family and feel the need to travel to their parent’s and grandparent’s homeland.

The image of the woman in the hijab spoke to me of Dukkha, the first of The Four Noble Truths: that life is full of difficulties, suffering and impermanence. This notion seems an exaggeration. Certainly life does not demand suffering, but now in middle age I admit to palpably understanding impermanence. It has become obvious, painfully so. Maybe this is the message.

Still I think this is too grim an interpretation. Too grim even though I recall telling my father, with his cachectic face starring back at us from the hospice bathroom mirror, that there is no cure and no hope. This is the definitive reason not to waste one second drinking bad wine, thinking petty thoughts, wasting a sunny day or for that matter a rainy one. If we approach our life like this…well, maybe when our time comes we can pass without suffering.

Volume 5742 (15), 1/1/2009